Sharpshooter, Educator, Nurse, Hero: The 19th Century Gutsiness Of Yamamoto Yae

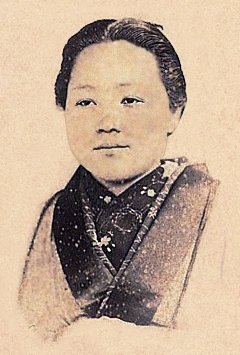

“Article Four: The words of women and girls are to be utterly disregarded.” Yamamoto Yae probably heard these words from an early age. They were read before her community’s assembled samurai at least once a year. Her brothers and father would have studied them closely in their education as vassals to the Matsudaira clan of Aizu. The words were part of the clan code, guidelines for both clan society and government that served as what we might today call a constitution.Yae lived her life in a way that utterly disregarded Article Four. She’s been a local hero in her hometown of Aizu-Wakamatsu — still a city in western Fukushima Prefecture — for decades. More recently, she’s attracted national and international attention thanks to popular depictions. She was a soldier, shooting instructor and feared sharpshooter in the Japanese Civil War, a fearless educator in the face of discrimination, a co-founder of one of Japan’s modern universities and a tireless advocate for the voices of her vanquished community.She was gutsy. She was persistent. And with a Spencer repeating carbine, she was lethal.***Aizu-Wakamatsu is an old castle town at the intersection of five roads. Nestled as it was in the far-off mountains of northern Japan, the war that gripped the country in 1868 might’ve seemed far away as summer turned to autumn that year. But to 22-year-old Yae, the war had already taken a toll. Her two brothers, Kakuma and Saburo, had been missing in action since the fighting began and were presumed dead. As the clan’s hereditary gunnery instructors, they’d been at the forefront of its armies. In their absence, Yae and her parents prepared for war as the Imperial Japanese Army pushed through the mountains, beating back other clans friendly to Aizu, and descended on the town.

Yamamoto Yae probably heard these words from an early age. They were read before her community’s assembled samurai at least once a year. Her brothers and father would have studied them closely in their education as vassals to the Matsudaira clan of Aizu. The words were part of the clan code, guidelines for both clan society and government that served as what we might today call a constitution.Yae lived her life in a way that utterly disregarded Article Four. She’s been a local hero in her hometown of Aizu-Wakamatsu — still a city in western Fukushima Prefecture — for decades. More recently, she’s attracted national and international attention thanks to popular depictions. She was a soldier, shooting instructor and feared sharpshooter in the Japanese Civil War, a fearless educator in the face of discrimination, a co-founder of one of Japan’s modern universities and a tireless advocate for the voices of her vanquished community.She was gutsy. She was persistent. And with a Spencer repeating carbine, she was lethal.***Aizu-Wakamatsu is an old castle town at the intersection of five roads. Nestled as it was in the far-off mountains of northern Japan, the war that gripped the country in 1868 might’ve seemed far away as summer turned to autumn that year. But to 22-year-old Yae, the war had already taken a toll. Her two brothers, Kakuma and Saburo, had been missing in action since the fighting began and were presumed dead. As the clan’s hereditary gunnery instructors, they’d been at the forefront of its armies. In their absence, Yae and her parents prepared for war as the Imperial Japanese Army pushed through the mountains, beating back other clans friendly to Aizu, and descended on the town. On the rainy morning of October 8th, crowds jammed Aizu-Wakamatsu’s streets after the alarm bells rang. Friendly forces were on the run, and the enemy was coming. Like many others, Yae ran to the castle’s safety. Unlike them, she ran with a load of rifles under each arm. The war had, at least somewhat, changed Aizu society: In the preceding weeks, Yae had taught young samurai boys, with whom she never could have studied, how to shoot and march. Kakuma had been her teacher, but she’d developed her own approach to gunnery and artillery that was enhanced by her above-average physical strength.The imperial army grew to fear Yae during the ensuing monthlong siege because of her marksmanship, aided by the technological edge of a seven-shot repeating rifle. She took part in day and nighttime raids, helped command defensive actions and directed cannon fire. That she was a woman didn’t matter so much to the Aizu men anymore — and perhaps as further insurance against any potential complaints, she wore Saburo’s uniform. It was no disguise: She would’ve grown up with these men, and Aizu samurai prided themselves on stubborn adherence to what they saw as society’s proper order. This intractability didn’t matter. She proved herself to them in battle.Article Four’s words must have been far from their minds by the siege’s end: When the Aizu samurai surrendered and were marched off to POW camps, Yae marched with the men.***The war’s aftermath must have been bittersweet for Yae. Her father had died in battle on November 1st, but her brother Kakuma was alive and a prisoner of war in Kyoto, though he’d been blinded. After her own release, Yae and her mother relocated to Kyoto to start anew and to support her brother, who’d become a consultant to the city government following his own release. With his help, Yae found work as an instructor at the local girls’ school, which still survives as Kyoto Prefectural Oki High School.Like many defeated Aizu samurai in these years, Yae and her brother converted to Christianity in the immediate postwar years. Around the same time, Yae met a young American-educated samurai-turned-evangelist named Niijima Jo, who frequently consulted Kakuma. Not long thereafter, in 1875, Yae and Jo were married in the first Christian wedding ceremony in Kyoto.

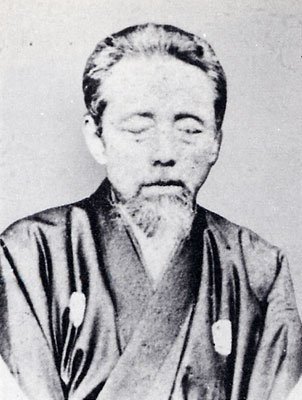

On the rainy morning of October 8th, crowds jammed Aizu-Wakamatsu’s streets after the alarm bells rang. Friendly forces were on the run, and the enemy was coming. Like many others, Yae ran to the castle’s safety. Unlike them, she ran with a load of rifles under each arm. The war had, at least somewhat, changed Aizu society: In the preceding weeks, Yae had taught young samurai boys, with whom she never could have studied, how to shoot and march. Kakuma had been her teacher, but she’d developed her own approach to gunnery and artillery that was enhanced by her above-average physical strength.The imperial army grew to fear Yae during the ensuing monthlong siege because of her marksmanship, aided by the technological edge of a seven-shot repeating rifle. She took part in day and nighttime raids, helped command defensive actions and directed cannon fire. That she was a woman didn’t matter so much to the Aizu men anymore — and perhaps as further insurance against any potential complaints, she wore Saburo’s uniform. It was no disguise: She would’ve grown up with these men, and Aizu samurai prided themselves on stubborn adherence to what they saw as society’s proper order. This intractability didn’t matter. She proved herself to them in battle.Article Four’s words must have been far from their minds by the siege’s end: When the Aizu samurai surrendered and were marched off to POW camps, Yae marched with the men.***The war’s aftermath must have been bittersweet for Yae. Her father had died in battle on November 1st, but her brother Kakuma was alive and a prisoner of war in Kyoto, though he’d been blinded. After her own release, Yae and her mother relocated to Kyoto to start anew and to support her brother, who’d become a consultant to the city government following his own release. With his help, Yae found work as an instructor at the local girls’ school, which still survives as Kyoto Prefectural Oki High School.Like many defeated Aizu samurai in these years, Yae and her brother converted to Christianity in the immediate postwar years. Around the same time, Yae met a young American-educated samurai-turned-evangelist named Niijima Jo, who frequently consulted Kakuma. Not long thereafter, in 1875, Yae and Jo were married in the first Christian wedding ceremony in Kyoto. Niijima Jo — also known by an Americanized name, Rev. Joseph Hardy Neesima — is still remembered in the annals of modern Japanese educational and religious history, though he often gets most of the credit for accomplishments he shared with his wife. Yae and Kakuma were equally forceful voices in fighting for the rights of Christians in Kyoto in those years, and in the drive toward founding a new school built around the educational model of Protestant schools in New England.Thus, Yae, Jo, and Kakuma ought to share in the credit for the 1875 founding of Doshisha, a once small private school which survives, in modern iteration, as Doshisha University.Doshisha wasn’t coed at its foundation, so an affiliated second school, Doshisha Girls’ School — now Doshisha Women’s College of Liberal Arts — was founded in 1876.The credit for that school goes to two women: Yae and British missionary Alice Starkweather.***After Niijima Jo died in 1890 at just 46 years old, Yae embarked on a new mission, joining Japan’s Red Cross and working as a military nurse. She cared for wounded soldiers in Hiroshima during the First Sino-Japanese War and in Osaka during the Russo-Japanese War while also advocating for improvements in the status and treatment of Army nurses. Decorated twice by the Japanese government, she also received recognition directly by the young Emperor Hirohito in 1928 for her educational and caregiving contributions.During her Doshisha days, but also in her final years, Yae remained an outspoken advocate for and protector of the ex-Aizu samurai community. More than a few former Aizu warriors came to Kyoto and worked for Doshisha, or moved on to other locales, and even the old lord’s family consulted Yae. In the latter role, she was part of a relatively small circle of former Aizu samurai. Some of them were related to her, but all of them probably would’ve blanched, in the old days, at being anything close to an equal with a woman.

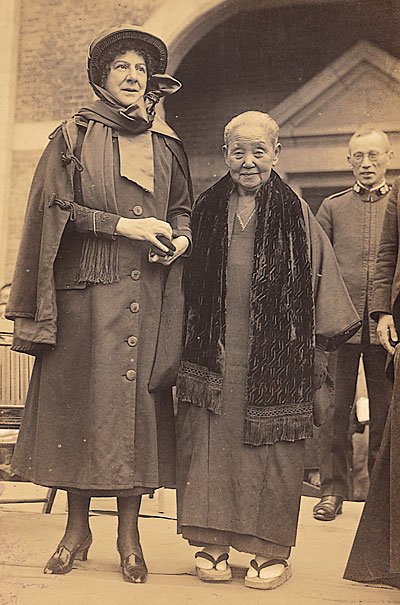

Niijima Jo — also known by an Americanized name, Rev. Joseph Hardy Neesima — is still remembered in the annals of modern Japanese educational and religious history, though he often gets most of the credit for accomplishments he shared with his wife. Yae and Kakuma were equally forceful voices in fighting for the rights of Christians in Kyoto in those years, and in the drive toward founding a new school built around the educational model of Protestant schools in New England.Thus, Yae, Jo, and Kakuma ought to share in the credit for the 1875 founding of Doshisha, a once small private school which survives, in modern iteration, as Doshisha University.Doshisha wasn’t coed at its foundation, so an affiliated second school, Doshisha Girls’ School — now Doshisha Women’s College of Liberal Arts — was founded in 1876.The credit for that school goes to two women: Yae and British missionary Alice Starkweather.***After Niijima Jo died in 1890 at just 46 years old, Yae embarked on a new mission, joining Japan’s Red Cross and working as a military nurse. She cared for wounded soldiers in Hiroshima during the First Sino-Japanese War and in Osaka during the Russo-Japanese War while also advocating for improvements in the status and treatment of Army nurses. Decorated twice by the Japanese government, she also received recognition directly by the young Emperor Hirohito in 1928 for her educational and caregiving contributions.During her Doshisha days, but also in her final years, Yae remained an outspoken advocate for and protector of the ex-Aizu samurai community. More than a few former Aizu warriors came to Kyoto and worked for Doshisha, or moved on to other locales, and even the old lord’s family consulted Yae. In the latter role, she was part of a relatively small circle of former Aizu samurai. Some of them were related to her, but all of them probably would’ve blanched, in the old days, at being anything close to an equal with a woman. Yae died in 1932. Her funeral drew an attendance of 4,000 — nearly the size of the old Aizu clan army — and at her request, renowned journalist Tokutomi Soho wrote her epitaph.For a gutsy combat veteran turned teacher turned nurse from the depths of rural Japan, it seems a fitting farewell.About the author:

Yae died in 1932. Her funeral drew an attendance of 4,000 — nearly the size of the old Aizu clan army — and at her request, renowned journalist Tokutomi Soho wrote her epitaph.For a gutsy combat veteran turned teacher turned nurse from the depths of rural Japan, it seems a fitting farewell.About the author:

Nyri A. Bakkalian is a young historian specializing in Japanese and military history, trained under the tutelage of renowned political historian Richard Smethurst. She has a soft spot for local history and unknown stories, preferably uncovered during road trips. When not hunting for unknown history, Nyri can most often be found sketching while enjoying a good cup of Turkish coffee. Follow her on Twitter at @riversidewings.

Nyri A. Bakkalian is a young historian specializing in Japanese and military history, trained under the tutelage of renowned political historian Richard Smethurst. She has a soft spot for local history and unknown stories, preferably uncovered during road trips. When not hunting for unknown history, Nyri can most often be found sketching while enjoying a good cup of Turkish coffee. Follow her on Twitter at @riversidewings.